Floyd Mccree

|

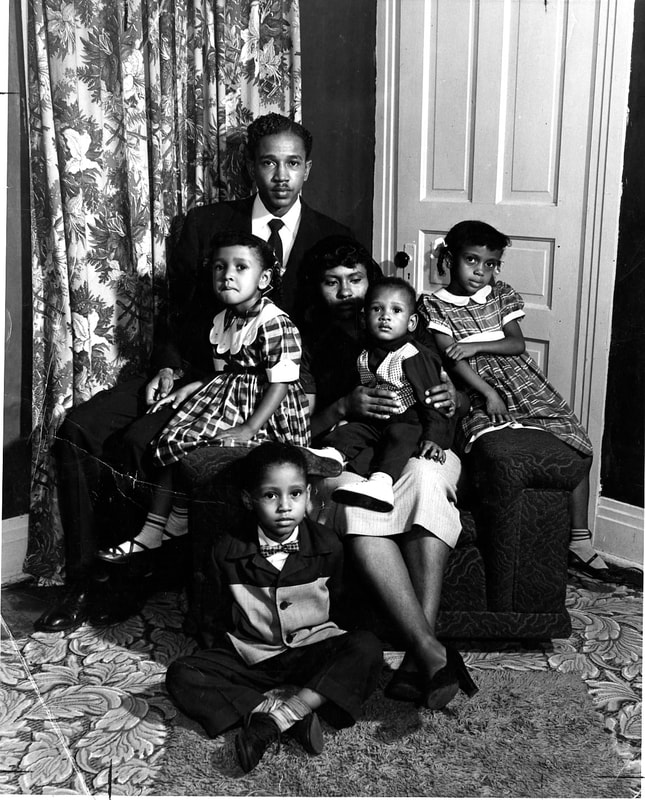

Floyd McCree was born in Webster Grove, Missouri on March 29, 1923. He grew up in St. Louis and eventually graduated from Lincoln University, a historically black university in Missouri. After college McCree served in the army during WWII in the South Pacific and rose to the rank of staff sergeant. Like many men coming home for WWII, McCree was looking for well paying work as manufacturing jobs turned from producing machines of war back to their civilian pursuits. He was hired at the Buick foundry and moved to Flint. The foundry had been a starting point for black workers in Buick since the early twentieth century when the lack of safety protections and union support made foundry jobs especially dangerous and undesirable. It was still difficult though less dangerous work in the 1940s and 50s but McCree was dedicated and, just like in the army, quickly climbed through the ranks. He was promoted to foreman and ultimately supervisor of maintenance.

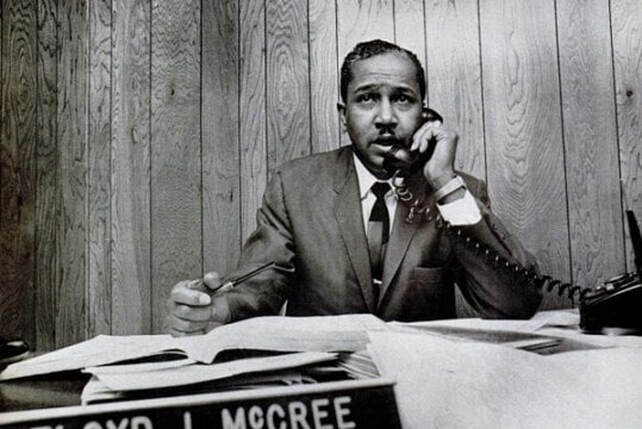

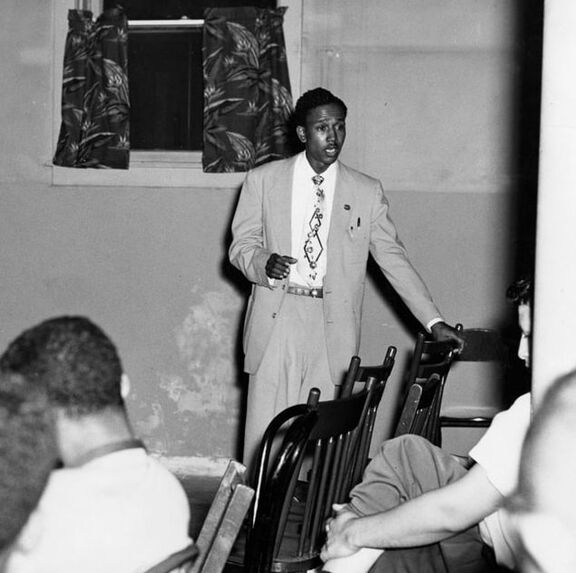

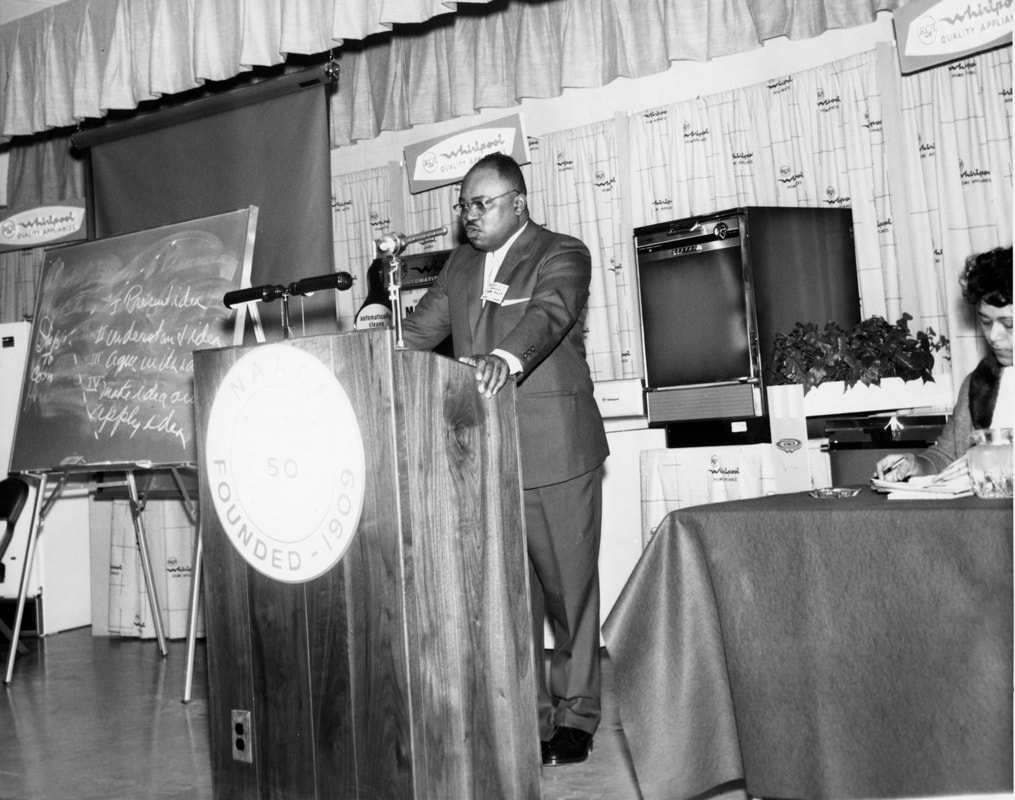

It was at the Buick foundry that Floyd McCree met civil rights leader Edgar B. Holt. Holt began at Buick in 1950, also a WWII veteran of Pacific theater. Together Holt and McCree became involved with organizing a union bargaining committee to obtain equal pay and rights for black employees which became known as the Foundry Council. Holt would be McCree’s campaign manager during his first unsuccessful run for City Commission in 1954. Holt believed in McCree though and continued to manage his political campaigns. McCree was successful in 1958 in securing a seat on the City Commision representing the 3rd Ward. In 1966, the City Commision appointed Floyd McCree mayor of Flint.

|

The controversial claim

There is some controversy to the claim that McCree was the first black mayor in America. McCree is often referred to as one of the first black mayors, partly because during the Reconstruction period in the 19th century at least two black mayors were elected: Pierre Caliste Landry in Donaldsonville, Louisiana and W.B. Scott in Maryville, Tennessee. Thomas Henthorn, history professor at the University of Michigan-Flint, pointed out in a 2015 article that though McCree was picked by the City Council, as was Robert Henry Clayton of Springfield, Ohio another mayor who often received the ‘first black mayor’ title, the first popularly elected black mayor was Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana. Hatcher was also elected in 1966 but took office after Cleveland, Ohio’s Carl Stokes. So Stokes is often referred to as the first popularly elected black mayor to be sworn in after Reconstruction. However, Floyd McCree’s Flint was a much larger city than Cleveland, Springfield, or Gary. Flint was the 62nd largest city in America, so many still remember him as the first black mayor of a major city post-Reconstruction.