1918 SPANISH Flu Epidemic

|

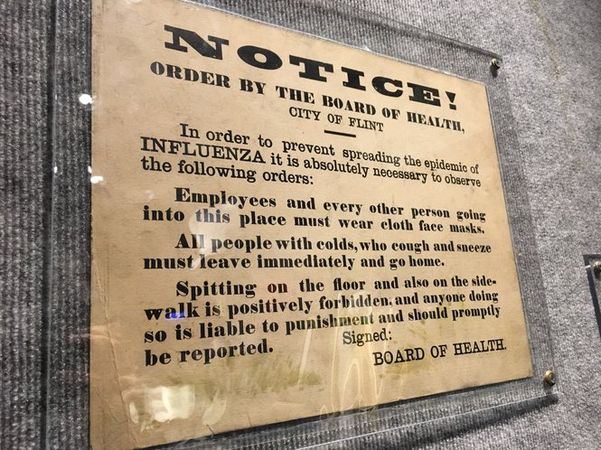

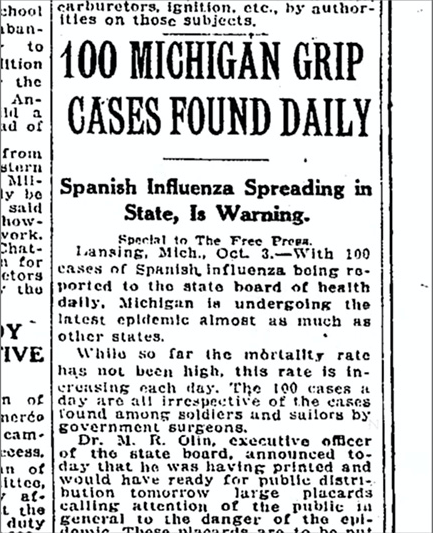

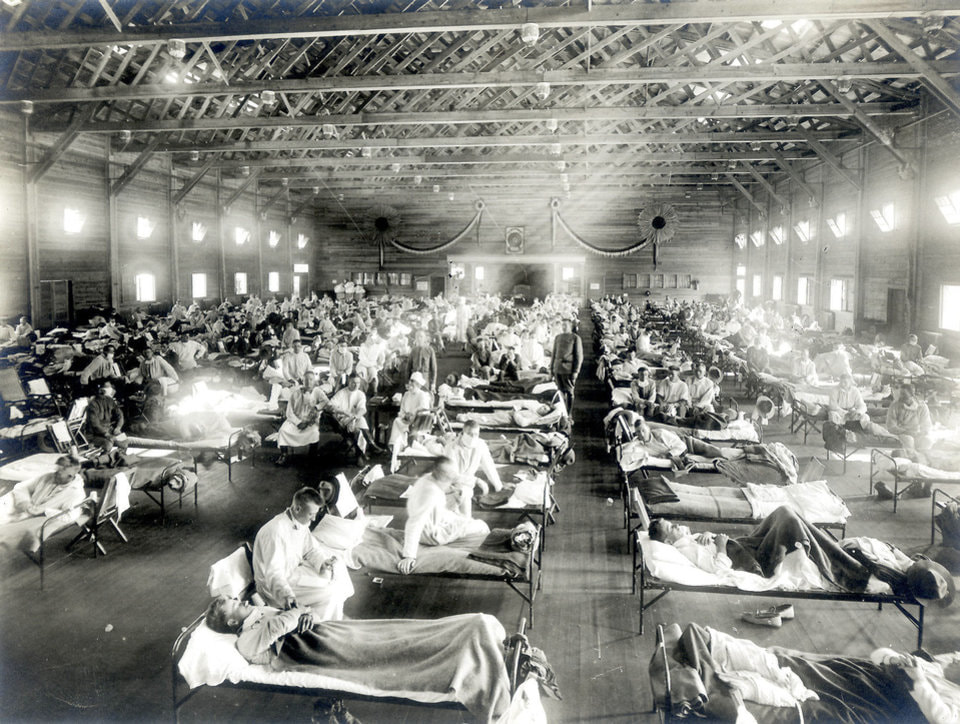

Lessons Learned from the 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic

We are living through a harrowing, once-in-a-century event, the spread of a virulent virus. As human beings have begun living mostly in high population density urban areas, the control of the spread of infection has become vital to the continued existence of modern society - as the recent months of isolation and closures in order to “flatten the curve” have shown. We learned this lesson the hard way in America in 1918 during the Spanish Flu epidemics second and deadliest wave which, is estimated to have infected 500 million people worldwide and killing around 50 million. |