The League of Gentlemen Scandal

|

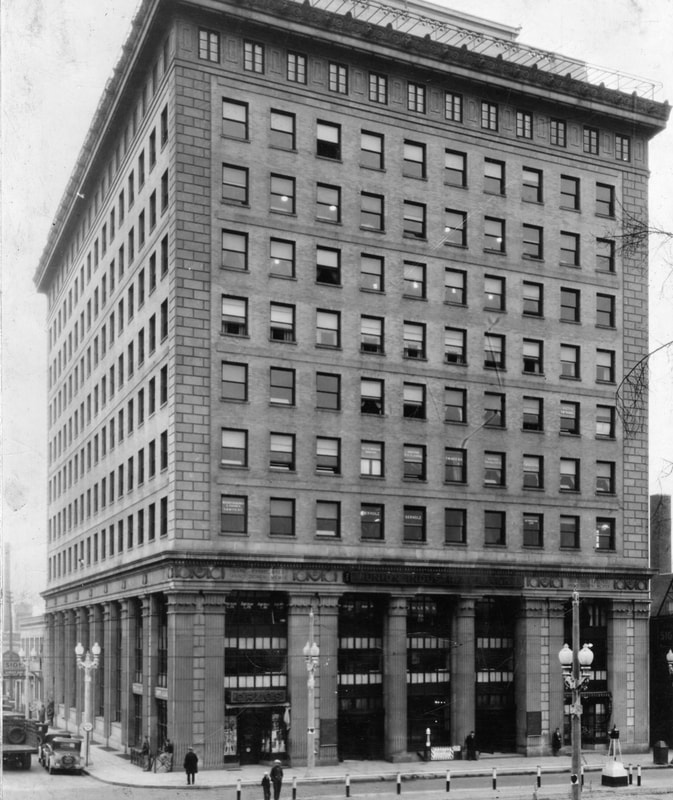

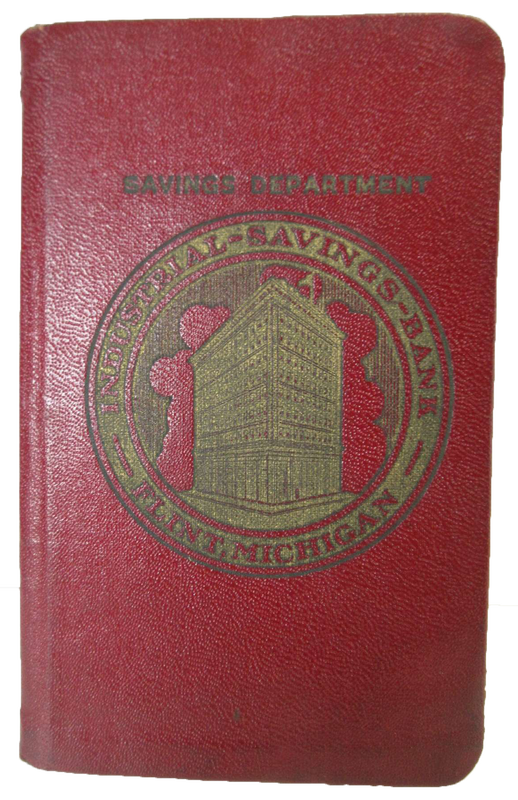

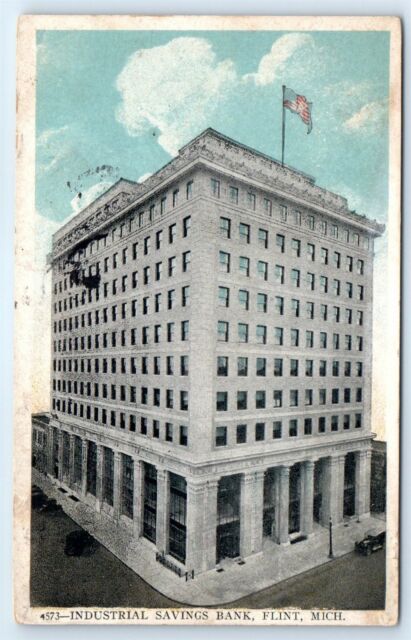

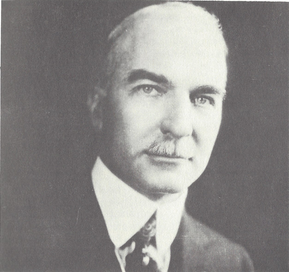

They Were No Gentlemen Inside the warm and welcoming mahogany paneled confines of the Flint Industrial Savings Bank, the dapper bank executives crowded around an impressive heavy conference table. Outside, the autumn winds were blowing that October of 1929, and soon a seismic change across America and the world would blow in, as well. Inside the conference room, though, the executives’ designer leather shoes were as dry as their afternoon martinis, while the smiling visage of the Chairman of the Board of Directors, Charles Stewart Mott, looked down on the assemblage, from his portrait, hung with care in the room. But, this was no ordinary bank meeting. Rather, this was a conclave of the “League of Gentlemen”, the ironic and secret moniker the group had selected to identify themselves. No one from the outside could know…because this group was no ordinary group of bankers. They were, in fact, in the very middle of perpetrating the biggest bank fraud the United States of America had ever witnessed. Together, they would steal the 2021 equivalent of nearly 58 million dollars. |

|

With minimum rules of engagement, and tactics that would soon be deemed illegal and usury in the 1930’s, millions of people worldwide were riding the rolling wave of irrational and careless exuberance. They made easy targets. By using a series of strategies, The League of Gentlemen had been systematically stealing depositors’ cash, to speculate in the wild Roaring 20’s stock market roller coaster.

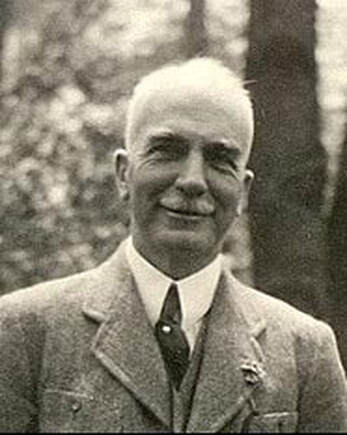

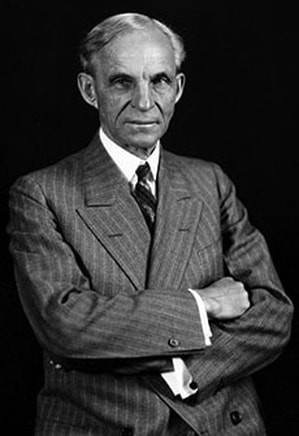

They leveraged the old school “fake note” scheme, which required tight teamwork and skillful forgery. Another scam was to obtain bills and drafts destined for other banks and just filch them. They’d write out an IOU in the name of some local celebrity type, lying that those folks owned the shares, and claiming they were on deposit at the Flint bank. Then they’d attach the share certificates to the promissory notes as proof. The finishing touch was a forged signature. Then, the bank would loan money to the other “Gentlemen”--not the folks whose names they’d forged. The gang had become so brazen they were even using Mr. Mott as one of their celebrity victims, forging his name freely. Along with Mott, they forged GM and Chevrolet founder William C. “Billy” Durant’s name. When they ran out of local luminaries, they started going outside of Flint. Sticking with their auto industry theme, they faked Henry Ford documents, too. Sometimes, they’d simply rob safe deposit boxes, stealing the money like convenience store thugs--albeit in very nice suits and matching ties and shoes. They were gentlemen after all. |