Before we can explore that, we need to have an understanding of the stage on which that drama would play out. We need to go back to 1800’s America, where tensions over slavery had created not only a societal crisis, but a genuine Constitutional crisis as well.

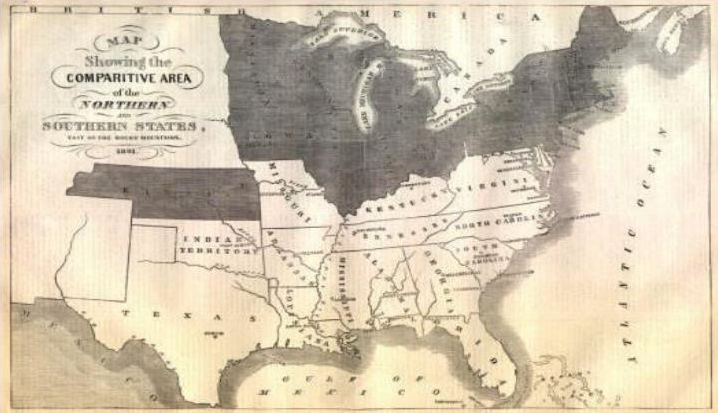

The missouri compromise |

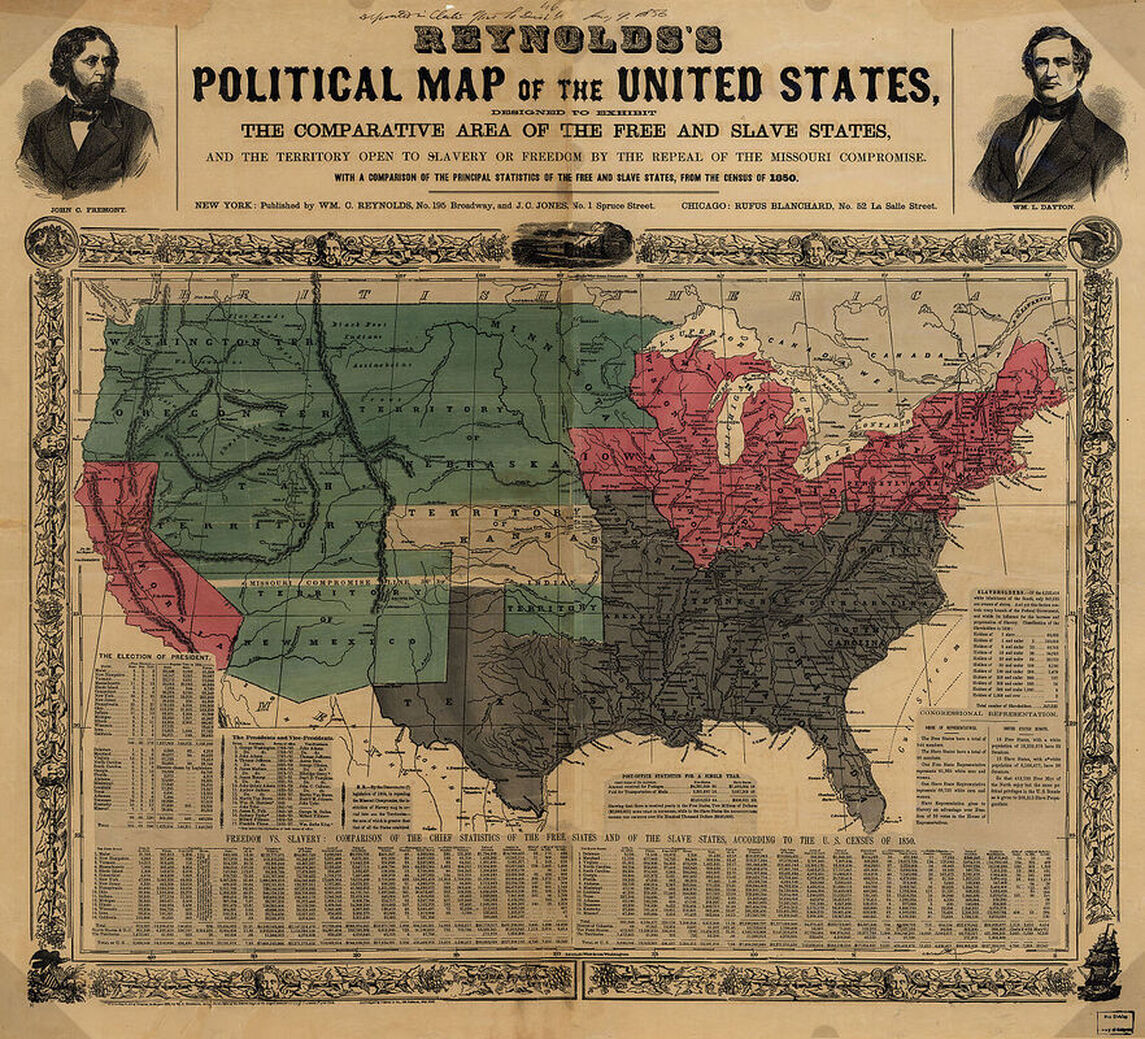

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 drew a line between North and South at 36 degrees, 30 minutes north latitude, with slavery permitted south of the line and completely forbidden north of it. The one exception was the new slave state of Missouri. Conflict intensified as Northern states grew more anti-slavery, and the South hardened its pro-slavery culture in to a religious fervor.

The North increasingly refused to honor all accommodations for slavery, refusing to let Southerners even travel through their borders with slaves--not even for a moment. The South returned the favor by refusing claims of freedom to slaves who had spent time traveling with their masters in the North. That situation had previously entitled a slave to a claim of freedom. In fact, this circumstance is precisely where the Flint nexus resides. |

Thomas Stockton and his Connection with Flint

|

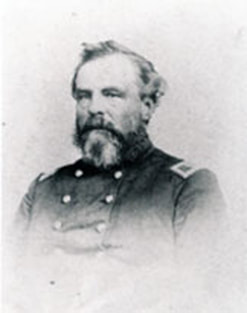

Thomas Stockton is a somewhat famous Flint name. His home still stands in the city, now known as “The Stockton Center at Spring Grove”, which is a non-profit organization and a museum.

Stockton was born in 1805, in New York’s Catskill Mountains. His family had a deep connection to young America. The Colonel’s family lineage is rich with history. His cousin Richard Stockton was a signer of The Declaration of Independence, and his grandson was Commodore Robert F. Stockton, who was a senator, slave owner, and 1812 naval war hero. So, it wasn’t surprising when Thomas Stockton chose a military career, attending West Point. He went on to serve at the Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, and later Fort Snelling in Wisconsin Territory (today’s St. Paul, Minnesota), under Zachary Taylor, who went on to be a war hero and President. When Stockton was stationed in Minnesota, he met his future wife, Maria Smith. She was the teen daughter of a very important Flint citizen, Flint’s first white settler, Jacob Smith. It was land that Maria inherited from her father which ultimately brought her and her husband, Colonel Stockton, to Flint. |

Rachel's Story

ON THE FRONTIER WITH THE STOCKTON FAMILY

Before the Stocktons ever arrived in Genesee County, in the spring of 1830, Maria and Thomas were married with a child coming along, shortly thereafter.

To assist with the domestic work in his absence, like many other military officers, Stockton purchased a slave, a teenaged ‘mulatto’ girl named Rachel, who became Stockton’s property in St. Louis that fall.

This wasn’t at all unusual for the time as many northern forts were also surrounded by enclaves of slaves. Indeed, Stockton’s own brother-in-law, John Garland (whom Garland Street in Flint was named), was also a slave owner.

So it was that over the next four years, the Stocktons brought Rachel with them to Fort Snelling, and then to Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien in the Michigan Territory, as well as to trips to and from Washington.

During these years, Rachel became pregnant and gave birth to a son John Henry. The paternity of John Henry is unknown, but after this occurred, Stockton decided he no longer needed a slave. His only written comments about the transaction were “ I sold Rachel, having taken her with me to St. Louis for that purpose.”

After several stops along the way, Stockton finally headed to Flint, along with John Garland and other heirs of Jacob Smith (who had died in 1825), to claim their inherited land.

To assist with the domestic work in his absence, like many other military officers, Stockton purchased a slave, a teenaged ‘mulatto’ girl named Rachel, who became Stockton’s property in St. Louis that fall.

This wasn’t at all unusual for the time as many northern forts were also surrounded by enclaves of slaves. Indeed, Stockton’s own brother-in-law, John Garland (whom Garland Street in Flint was named), was also a slave owner.

So it was that over the next four years, the Stocktons brought Rachel with them to Fort Snelling, and then to Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien in the Michigan Territory, as well as to trips to and from Washington.

During these years, Rachel became pregnant and gave birth to a son John Henry. The paternity of John Henry is unknown, but after this occurred, Stockton decided he no longer needed a slave. His only written comments about the transaction were “ I sold Rachel, having taken her with me to St. Louis for that purpose.”

After several stops along the way, Stockton finally headed to Flint, along with John Garland and other heirs of Jacob Smith (who had died in 1825), to claim their inherited land.

rachels gains her freedom

|

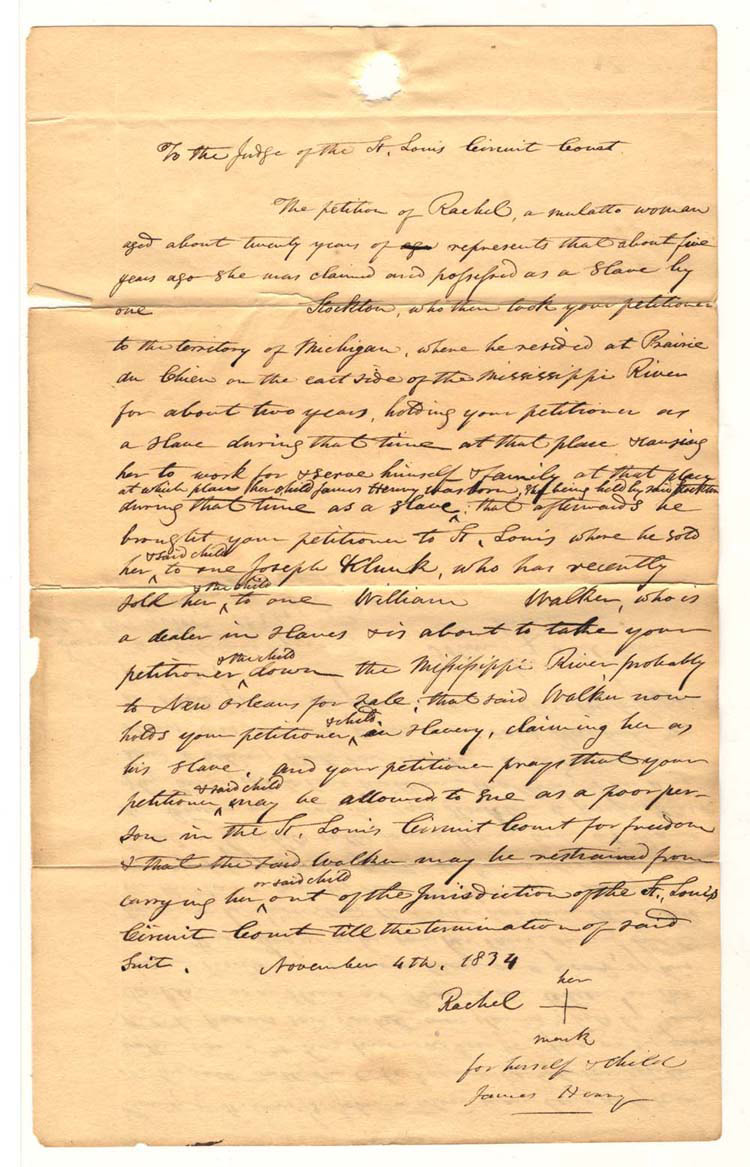

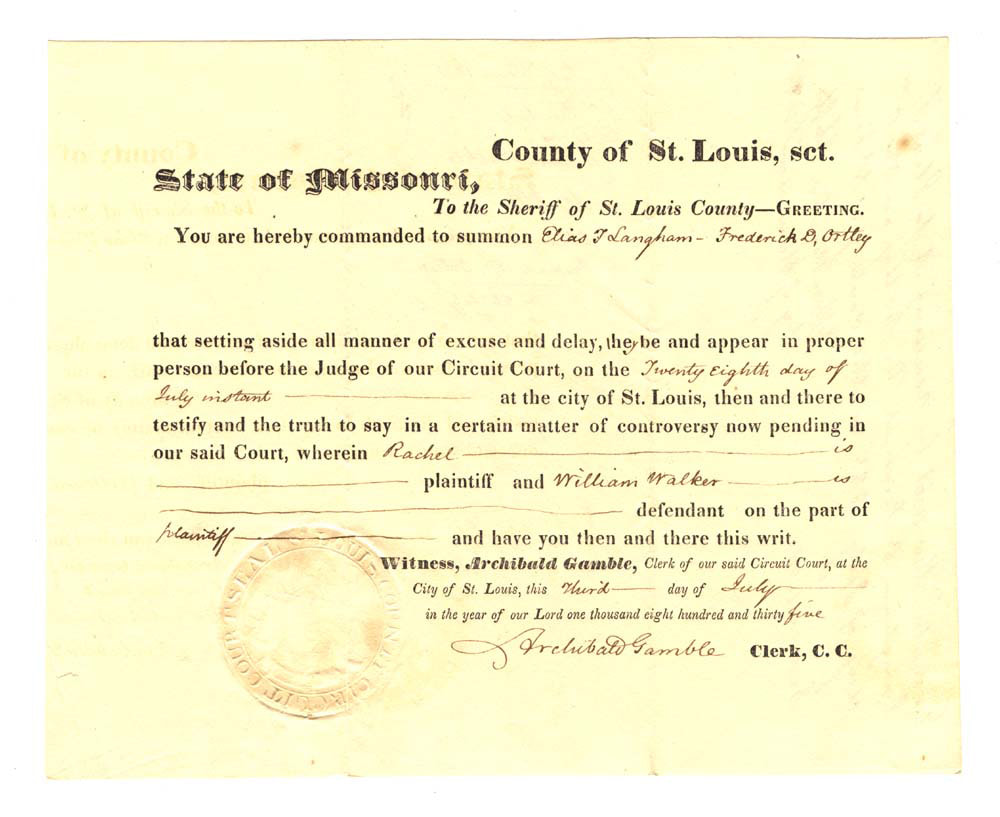

As the Stockton's moved on, Rachel's impossible situation was playing out in St. Louis. She and her child had been quickly sold again, this time to a slave dealer named William Walker, who was according to Rachel, “beating and abusing” her. Moreover, she feared that he would soon “sell her and her son down the river” to New Orleans.

Her plight caught the attention of kind abolitionists, who understood the legal system and wanted to change her fate. They helped her start a legal action to secure her and John Henry's freedom, by utilizing a 1824 Missouri state law, which entitled slaves to file suit as "poor people". To bolster the case against Walker, Rachel's court-appointed counsel, Josiah Spalding, contacted Colonel Stockton in Flint to obtain verification. Stockton responded, sending a letter describing Rachel as a “personal servant” for his family, and explaining how he took her to what ultimately became Wisconsin and Minnesota, and then Washington D.C. before finally selling her. With Stockton confirming her travels, Rachel’s attorney’s argued that since she had been brought to free soil by Stockton, she was in fact now a free person. Stockton had “no right” they maintained, to "extend slavery to a state where it was outlawed”. Walker’s lawyer argued, contrarily, that Stockton, as a United States Army officer, and with no personal say in his duty assignment, should not to have had to forfeit his property (Rachel), just because he had been temporarily detained in a place that was not his permanent residence, even if it was a free territory. His argument maintained that Rachel was still a slave. The Circuit Court agreed with this argument, and Rachel remained in bondage. Her counsel, however, persisted, appealing to the Missouri Supreme Court. Spalding's renewed arguments were strongly supported by the prevailing sentiment of the era that slavery was a dying institution and the notion that Rachel’s time on free soil did, in fact, constitute a change in her personal status. With this philosophy in play, and leaning on the 1824 case of Winny v. Whitesides, which had established the "once free, always free" precedent, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision, ruling in her favor in 1836. Rachel was free. Shortly thereafter, the decision in Rachel v. Walker became the basis to free her son. This was a truly significant and landmark case. Rachel v. Walker became a critical legal precedent that impacted American Constitutional law for the next two decades. Under the auspices of the legal principle of stare decisis (essentially an acknowledgment and affirmation of precedent), Rachel’s case became a lynchpin in other cases: a military officer lost all ownership rights when he took his slave to a territory that was free. |

Rachel v. Walker - the precedent in the dred scott caseTwenty one years later another slave would test these Constitutional waters, experiencing an entirely different result.

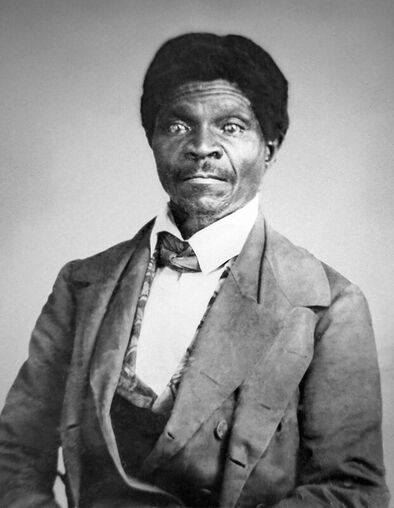

Dred Scott was the slave of Captain John Emerson, a doctor in the U.S. Army residing in Missouri, a slave state. Later, for two years, he was posted to duty in Illinois, a free state, taking Scott with him. Emerson was then, coincidentally, transferred to the same fort that Stockton had been previously sent to, Fort Snelling in Wisconsin Territory, present day St. Paul, Minnesota. There, slavery was prohibited by the Missouri Compromise. While at Fort Snelling, Scott married Harriet Robinson, the slave of another government official posted to the Fort. They had two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, both born in free territory. Ultimately, they all returned to Missouri with Emerson, now the owner of the entire family. |

After Emerson died, Scott, aided by abolitionist friends, filed a lawsuit against Emerson’s widow to establish the family’s freedom. Rachel v. Walker had long since established the precedent for this action with Scott and his family having spent considerable time on free soil, and his children having been technically born with future freedom, virtually guaranteed by that precedent.

But times had changed since Rachel’s case. The nation was engaged in an increasingly bitter and vicious debate over slavery. Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat, authored a bill, named “An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas”, (more commonly remembered as the Kansas-Nebraska Act), which provided for the territorial governments in Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether there should exist slavery within their boundaries--in essence abandoning the Missouri Compromise. This law became the catalyst for the 1856 intersectional civil war, known as “Bleeding Kansas”. This sent shock waves through the nation, hardening positions both North and South.

Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner loudly criticized the “crime against Kansas”, infuriating South Carolinian Representative Preston Brooks to such a passion that he attempted to murder Sumner by cracking his skull with his heavy cane, while Congress was in session (and you thought politics were rough now). The stain where the blood pooled on the floor in the Capitol building can still be seen. Sumner survived, but with apparent cognitive impairment from the beating.

But times had changed since Rachel’s case. The nation was engaged in an increasingly bitter and vicious debate over slavery. Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat, authored a bill, named “An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas”, (more commonly remembered as the Kansas-Nebraska Act), which provided for the territorial governments in Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether there should exist slavery within their boundaries--in essence abandoning the Missouri Compromise. This law became the catalyst for the 1856 intersectional civil war, known as “Bleeding Kansas”. This sent shock waves through the nation, hardening positions both North and South.

Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner loudly criticized the “crime against Kansas”, infuriating South Carolinian Representative Preston Brooks to such a passion that he attempted to murder Sumner by cracking his skull with his heavy cane, while Congress was in session (and you thought politics were rough now). The stain where the blood pooled on the floor in the Capitol building can still be seen. Sumner survived, but with apparent cognitive impairment from the beating.

|

In to this fray enters the Dred Scott case. Losing their first case, his legal counsel tried again at the Missouri Supreme Court level. This time they changed tactics by filing suit against Mrs. Emerson’s brother, John Sanford, who had been legally responsible for Emerson's estate. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled against Scott, as well.

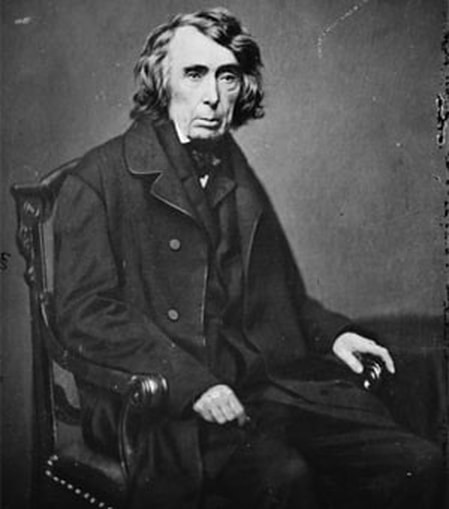

Finally, after 11 long years, in 1856, his case landed in the U.S. Supreme Court. The result of that suit would create a stench that hung over that apex of the United States federal judiciary branch, hastening the American Civil War. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote the majority opinion, asserting that blacks—free or slave—were not protected by the Constitution in any way, could not be citizens of any state, and therefore could not sue in federal courts, thereby nullifying Rachel v. Walker completely. Moreover, Taney wrote that under the Constitution blacks were regarded as “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race,” that they had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” But he didn’t stop there. Taney went on to say that “The enslaved African race are not intended to be included by the Declaration of Independence, and the right to hold them in slavery was “distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.” This was an abject lie, as there is no basis whatsoever for this assertion in the Constitution. While it did protect slavery in some respects, it didn’t do so in all respects, and provided no constitutional right to slavery. But it didn’t provide a Constitutional right to freedom either. It allowed states to choose. It also provided for the recapture of fugitive slaves. Despite these unfortunate Constitutional protections, it fell far short of Taney’s claims. It also fell far short of history. Blacks had been free citizens in many states at the time of the Constitution’s ratification, fought for the nation during the Revolution, and held other free positions since that time. Taney’s dark and unconstitutional position was backed up by a fabricated concept called the doctrine of “substantive due process.” It was an absurd and contradictory notion. It was, however, used by Taney to go on to claim that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. In so doing, he made it legal to have unlimited slavery anywhere, with no recourse to slow it, mitigate it, or prevent it. |

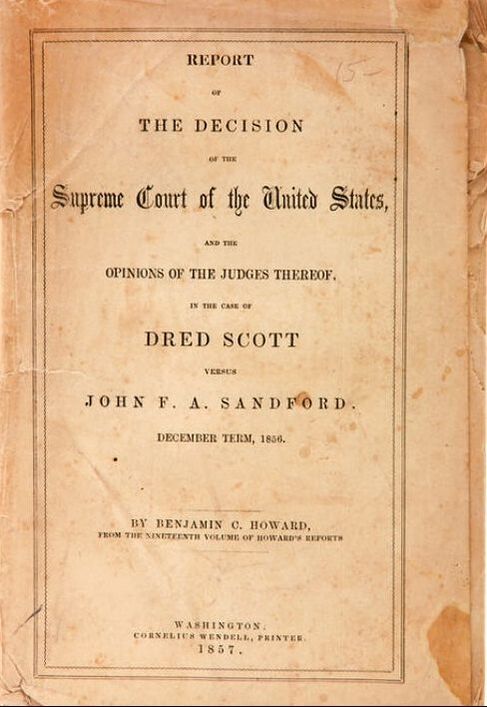

A published copy of the official Supreme Court decision from the Dred Scott report can be found in The Kinsey African Art & History Collection. In this official version of the report, Sanford’s name is misspelled as: “John F.A. Sandford. |

|

|

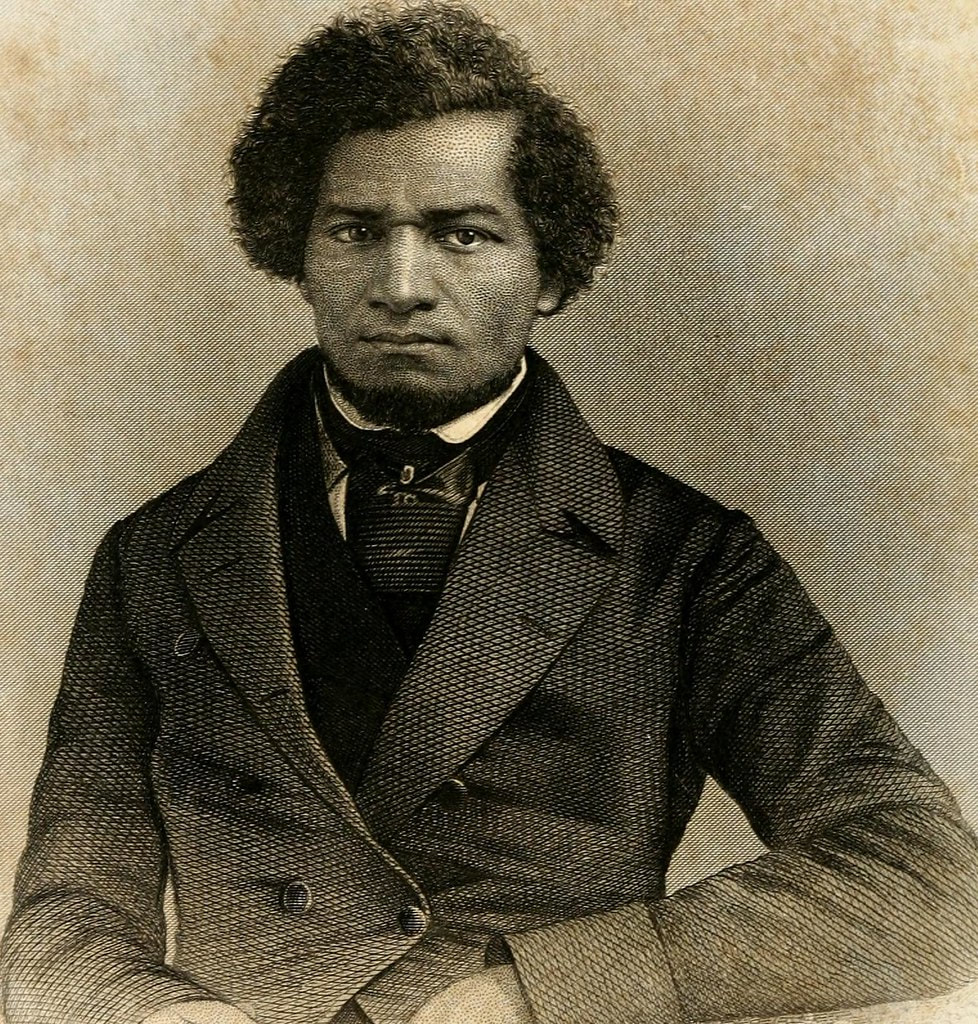

Dred Scott v. Sanford hit the nation like an electric surge. The nation’s leading black voice against slavery, Frederick Douglass was appalled by the decision, calling it a “vile and shocking abomination.” Still, he felt that “God and history were merely keeping the nation awake,” as “the Slave Power advanced too far, poisoning, and corrupting the institutions of the country, readying the people for “the lightning, whirlwind, and earthquake to come.”

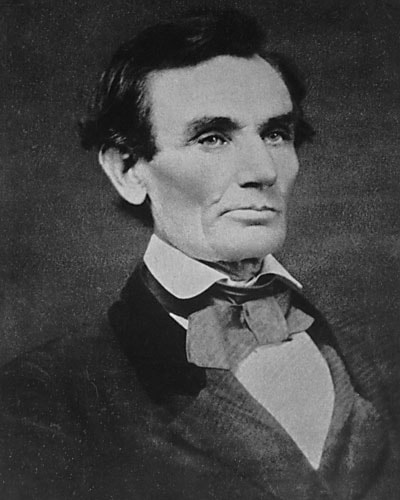

Abraham Lincoln found the Dred Scott decision ludicrous. A rising Illinois politician at the time, he argued that the decision was inconsistent with the established practices of the nation since the moment the Constitution was adopted in 1789, and before that, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and subsequently in 1789. Lincoln found the Scott decision to be the complete converse in terms of the beliefs of the founding fathers. Lincoln went on to say that the Dred Scott decision wasn’t just wrong, it was “an astonisher in legal history.” He argued that the Supreme Court’s legally incorrect and morally bereft decisions did not bind Congress or the President in their independent exercise of their own constitutional powers. Lincoln would go on to enact this belief as the 16th President of the United States, during the Civil War. What started with Colonel Stockton and Rachel and accelerated with Dred Scott, would ultimately be decided on the battlefields of America, but not by court cases. Instead, the matter would be definitively decided by ordinary American citizens, fighting under the Union banner, led by Abraham Lincoln, and Generals U.S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. It would be a final decision, irreversible by any court. A cause, that began with a woman named Rachel and a man named Stockton, whose roots are deeply embedded in Flint, followed a path that finally led to war.

After many brutal battles, a four-year bloody conflict, and more than 620,000 dead men, the nation and the world would be forever transformed. |

|

Sources:

Interviews with Kim Crawford, October 10th and 14th 2020 The 16th Michigan by Kim Crawford StocktonHouseMuseum.com The Daring Trader by Kim Crawford Fateful Lightning by Alan Guelzo Prophet of Freedom by David Blight Historic Fort Snelling in Art and Photos from the 1820s to Today St. Louis Circuit Court Historical Records Project: 1834 Nov Case Number 82 - Rachel, a woman of color v. Walker, William, accessed 26 January 201 (Searchable database in the Missouri History Museum's research center: online freedom suits.) The Law that Ripped America in Two, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-law-that-ripped-america-in-two-99723670/ http://www.thekinseycollection.com |

Written by: Gary L. Fisher

About Gary: A man of many talents, Gary runs a wealth advisory office in downtown Flint, he is a Flint historian, the radio host of Fish & the Flint Chronicles, and President of the Genesee County Historical Society. |